this is an article from 2018Oz Failure

The Australian festival scene has long been the biggest challenger to Edinburgh’s crown. Yet this year something went very wrong down under. DERWENT CYZINSKI reports.

Perth

Where did all the money go?

Of the Australian big three, Perth has long been the favourite of visiting comedians. “They’re more Brit and Irish than the people in Adelaide or Melbourne,” says Irish comic Mary Bourke. “They’re not too cool for school. They know how bogan they are and have no pretension.”

There’s little point filling a room with lovely people, though, when unlovely people make all your cash disappear. This year the Perth Fringe is in crisis after the private company it installed to look after ticketing, Jump Climb, announced it was seeking voluntary administration leaving A$200,000 (about £114,000) in artists and technicians’ fees unpaid. Fringe World, Perth’s version of our own Festival Fringe Society, has offered £49,000 – its own cut of the takings – to help ease the pain.

Jump Climb blames “a combination of factors including a downturn in ticket sales, debtors going into receivership and the general economic slow-down”. This slow-down includes the collapse of the mining industry around Perth and stagnation in the wider Australian economy. But none of this explains what they’ve done with other people’s money.

Jump Climb blames “a combination of factors including a downturn in ticket sales, debtors going into receivership and the general economic slow-down”. This slow-down includes the collapse of the mining industry around Perth and stagnation in the wider Australian economy. But none of this explains what they’ve done with other people’s money.

The question now is whether Fringe World can redeem itself in time for next year. It is looking for a bailout from Perth’s city fathers and the Adelaide Fringe. It will need to start from scratch financially, in the face of a lot of acts vowing never to return.

Alastair Barrie, who was in Perth last year and so got away with his takings, says: “I found that if you flyer constantly, you can still do really well. I managed to average 40 a night which is fine. People complain because you can’t just turn up and print money now. Over the last few years there’s been a 50 per cent increase in outside acts, especially British.”

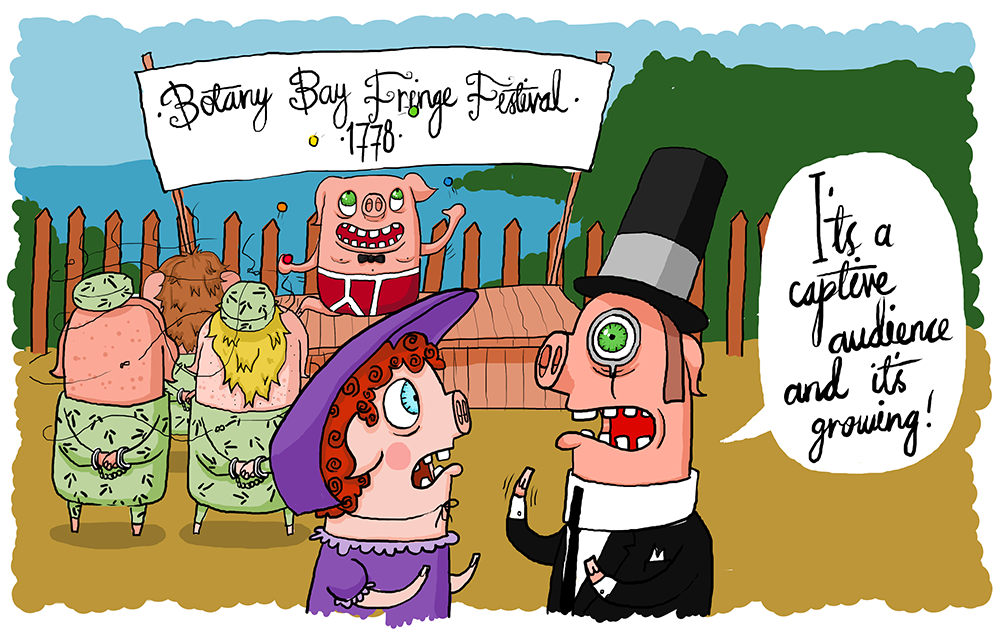

These acts have not brought more people. The downside to having a captive audience is that, when trying to build on it, there’s literally nowhere to go: Perth is is one of the most isolated urban centres on earth, with little outlying population.

Adelaide

Where did all the punters go?

Adelaide has the second largest Fringe festival in the world, despite the general opinion of Brit comedians that it’s the most boring town on the continent. Its biggest party now seems in question after a Fringe season Brendon Burns called “A terrible festival – the worst by a long shot”.

Adelaide has the second largest Fringe festival in the world, despite the general opinion of Brit comedians that it’s the most boring town on the continent. Its biggest party now seems in question after a Fringe season Brendon Burns called “A terrible festival – the worst by a long shot”.

If Perth suffered from spreading a good crowd too thin, the audiences in Adelaide just failed to turn up at all. “Nine shows in and my total sales across my entire run are still 50 per cent of my opening night sales in Perth” posted Alexis Dubus, perhaps better known as sarcastic Frenchman Marcel Lucont, at this year’s Fringe. “Having visited Adelaide before, I was blown away by how much this sleepy town got behind weird and wonderful offerings. Seven years on and those people seem to have vanished.” Brendon Burns stated “I lost count of the number of times I bumped into world-class international acts, declaring they would never return. I certainly won’t.”

“It was awful,” agrees Seymour Mace. “The people running it just kept banging on about how it was the second biggest Fringe after Edinburgh. Well it’s not the size that matters; it’s making it work. Edinburgh is a worldwide destination. In Adelaide the ONLY audience is local, and the more stuff you put on the less of them you have in each venue.”

Seymour suspects the Fringe’s organisers are indifferent to the acts’ experience. “There’s big maps in the street, but most of the venues aren’t on there. Ours wasn’t. They only care about the big official stuff, like Garden of Unearthly Delights and Gluttony. It’s just rich people running things for themselves and not giving a sh*t about anyone else.”

The City of Adelaide must take a share of the blame too. It schedules pretty much every bit of fun into one month – ‘Mad March’. The Clipsail 500 street race, the Writer’s Festival, the main Adelaide Festival of Arts, the Adelaide Cup horse race and numerous culinary and wino events leave the crowds jaded, divided, distracted and worse for wear.

“The audiences are drunk a lot of the time,” said Mary. “They’ll buy a ticket for a show just to get to a bar with no queue. Adelaide in March is like a war crime.”

Cabaret act Tomás Ford has criticised mega-venues such as the Croquet Club and the Garden of Unearthly Delights for “f*cking it up for everyone else” by turning the Fringe into a sort of beer tent with acts, rather than a cultural event with bars.

Henning Wehn thinks it has outgrown itself. “The Garden of Unearthly Delights used to be a nice little garden back in 2010,” he says. “Now it’s like Hampstead Heath.”

There may be a more endemic problem, however, as voiced by Frank Ford, the Adelaide Fringe’s founding director. Last year he was questioned by Australia’s ABC News after culture snobs claimed that there was too much comedy for it to be a true ‘fringe’ anymore. Ford shared their grievance. “I was terribly concerned because all of a sudden, they were swamping the Fringe,” he said. “It really looked like in the late 1990s the Fringe was going to be swamped and become a comedy festival.” He assured the public that this crisis had now been averted by an upswing in more arty (and dare we say, farty) fringe fare.

Adelaide’s sniffy attitude is all its own, but a problem endemic there is growing in Edinburgh: the crowds are only going to the big stuff. And even the big stuff is having slow nights, which it weathers by ‘papering’ shows with free tickets – as Alexis recalls, “Sometimes to people waiting in line to buy an actual ticket for something niche that’s struggling to survive”.

Melbourne

Where did the ‘open festival’ idea go?

This is a strange, strange beast. Normally an international festival is either free to all comers (like a fringe) or it’s invitational. Somehow the Melbourne International Comedy Festival (MICF) receives tens of thousands of dollars from the State of Victoria to run an open festival, but actually runs what amounts to a closed shop.

This is a strange, strange beast. Normally an international festival is either free to all comers (like a fringe) or it’s invitational. Somehow the Melbourne International Comedy Festival (MICF) receives tens of thousands of dollars from the State of Victoria to run an open festival, but actually runs what amounts to a closed shop.

It is run by Susan Provan (pictured above); mention her name and the words ‘dictator’ and ‘cabal’ flow like Victoria Bitter in the sunshine. She’s not exactly a Melbornian Mugabe, but Boothby Graffoe once indecorously said on stage that Provan “has her vagina fastened over this city like a bottle top” and he hasn’t been seen in Melbourne since.

Over 23 years of Provan’s rule the state-sponsored festival has run all the main central venues, with its flagship at the Town Hall. It has a vast budget with which to invite the cream of international talent, with hotel rooms, blanket publicity and the acts’ faces on city trams.

Other, smaller venues can bring people over too, if they fancy competing with the state behemoth. But stories abound of MICF meddling. Dan Willis, who runs independent venues with Scot Alan Anderson, says “There were attempts to have my acts’ visas turned down; sometimes because Susan doesn’t like them politically and sometimes because MICF wanted to bring them in later. Our show listings would get changed too.”

It’s well known that Provan dislikes taking on any act that has already been to Melbourne in a non-MICF venue. Henning visited the festival as a freelancer in 2012 with his sometime comedy partner Otto Kuhnle. He recalls: “At the end of the festival Otto and I had enjoyed a good run and had been nominated for the Barry Award; Melbourne’s main comedy gong. So we expected to be invited back as part of the main event. We never did.”

Success was all the more surprising given the barriers erected. “Every day we’d get a sales report at 2pm. The numbers were always good but we soon noticed that, at night when the show started, there hadn’t been a single extra ticket sold since that 2pm report. I phoned the ticketing agent – the one put in place by MICF – and was told that after 2pm the people on the phones all go home. Only the MICF sales were automated, so if you were not in the Town Hall you couldn’t sell tickets after 2pm! After a lot of haggling they agreed to keep the lines open til 5pm just for us, as long as I didn’t tell anyone.

Success was all the more surprising given the barriers erected. “Every day we’d get a sales report at 2pm. The numbers were always good but we soon noticed that, at night when the show started, there hadn’t been a single extra ticket sold since that 2pm report. I phoned the ticketing agent – the one put in place by MICF – and was told that after 2pm the people on the phones all go home. Only the MICF sales were automated, so if you were not in the Town Hall you couldn’t sell tickets after 2pm! After a lot of haggling they agreed to keep the lines open til 5pm just for us, as long as I didn’t tell anyone.

“A person might suspect that Provan’s lot don’t want people to think an independent model can work.”

Alastair Barrie says: “My feeling is, if you’re not part of Susan’s cabal you’re very unlikely to have a Barry judge visit you. She just doesn’t like being challenged. I had a very strange conversation with Susan where I was explaining I’d just done the Free Fringe in Edinburgh. She seemed to think that, over here, the Big Four venues are under attack, and that free-show people are ruining all the hard work they’ve put in.

“Everything is sewn up,” says Henning. “In Edinburgh everyone has a fair crack of the whip. I love Melbourne; the people are great and we had a right laugh. But I won’t return there until that monster goes.”